In the fitness world, intensity refers to “the rate at which an activity is being performed or the magnitude of the effort required to perform an activity or exercise.” Another way to think of it is how HARD you work at running, walking, cycling, swimming, weight-lifting or yoga.

I once spent an entire afternoon in the Outer Bank’s Pamlico Sound attempting to learn how to windsurf.

The board and sail I used were purchased to fit their owner, a guy friend who out-weighed, out-muscled and out-windsurfing-experienced me by miles; they were much too big for me.

But I didn’t care; not that the equipment was too big, nor that my experience was too small.

All I cared about was how fun and physically demanding (an irresistible combination for me) windsurfing appeared to be – and how no matter what, I was going to master it.

In one afternoon.

For hours my friend generously shared his experience, equipment, patience and time.

And for hours, I got up on the board, effortlessly balanced myself (shout-out to yoga), then worked like hell (the complete opposite of effortlessly) to position the sail in such a way as to catch the wind and glide smoothly across the sound.

Which never happened.

And even then I didn’t care.

I’d spent an entire afternoon tapping into nothing but my sheer physical strength and mental focus, pitting myself against the elements of nature and the laws of physics.

In the end, all that mattered was how intense and exhilarating that experience was; even my “attempt” at windsurfing did not disappoint.

And that’s what this week’s blog post is all about.

INTENSITY.

Let’s Review The FITT PRINCIPLE – And Focus on “I”

In Part II of this 6-part series I introduced the idea of the FITT PRINCIPLE; F = FREQUENCY, I = INTENSITY, T = TIME, and T = TYPE, shining a light on FREQUENCY.

Here in Part III I explore the second variable, INTENSITY, introducing you to what perhaps is a new concept to weave into your exercise routine.

Intensity is officially defined as an extreme degree of strength, force, energy, or feeling.

In the fitness world, intensity refers to “the rate at which an activity is being performed or the magnitude of the effort required to perform an activity or exercise.” Another way to think of it is how HARD you work at running, walking, cycling, swimming, weight-lifting or yoga. (1)

If you run fast or do sprints, speed walk or trek uphill vs flat, cycle uphill or at a high rate of speed, “sprint” swim from one end of the pool to the other, lift heavier weights or increase the number of repetitions, or participate in a “strength-based” yoga class, you’re adding intensity to your workout.

Essentially you’ve increased the rate at which you’re exercising, and that requires a greater magnitude of effort, aka INTENSITY.

How To Know How Hard You’re Working

It’s possible to take a simple measure of your personal “rate of exercise”.

For example, you could time how long it takes you to walk, run, cycle or swim one mile; less time = more intensity, or you could observe the amount of weight you lift during a strength training session; lighter weight = less intensity.

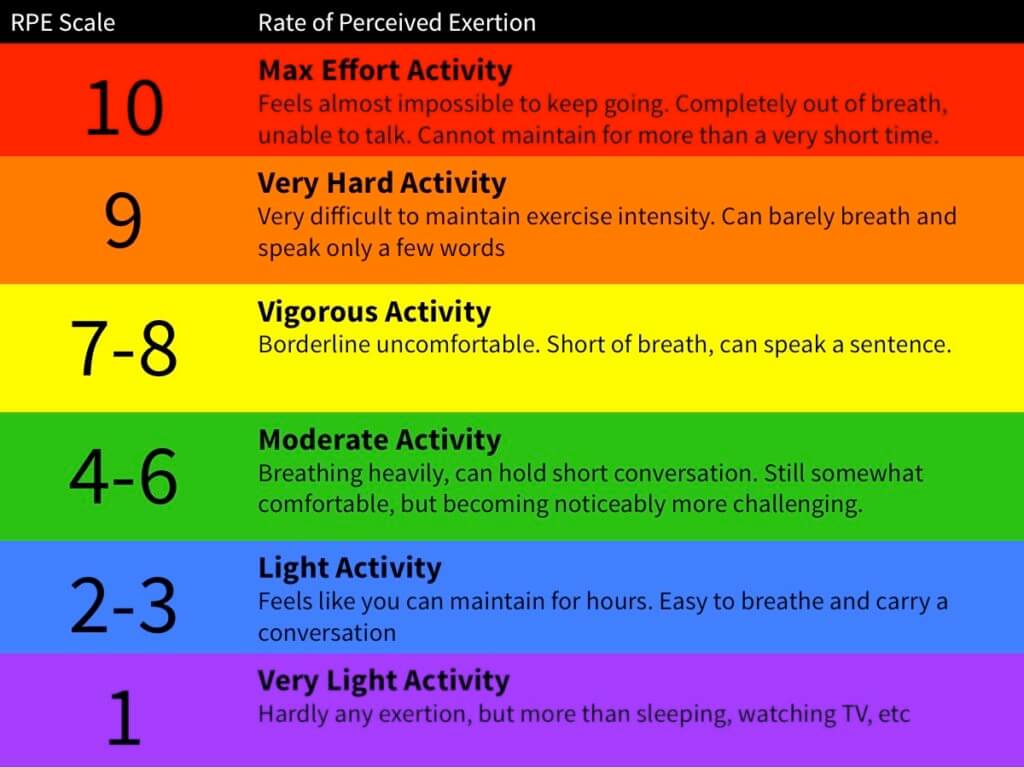

A more formal way to determine your personal rate of exercise is by using Rate of Perceived Exertion (RPE), a scale that measures exercise intensity from 1-10.

Exercising at level 1 feels like sitting quietly in a chair, while exercising at level 10 will leave you feeling quite uncomfortable. Use this guide to check in with yourself at different intervals of your workout. For example, when you begin your exercise routine you’re probably somewhere around level 2, but you’ll finish somewhere around level 7-8.

Regardless of whether you exercise on your own or with a partner, in a group, or one-on-one with a personal trainer, how intensely you work is up to you.

I always say, “You” put the “I” in INTENSITY.

To avoid injury or burnout, it’s critical to work at your own intensity level, keeping in mind that while it can be measured, intensity is also SUBJECTIVE.

To your best friend your idea of a “brisk” walk may feel like a leisurely stroll, and vice versa.

Does The LEVEL Of Intensity Matter?

When you’re first diagnosed, the intensity level at which you can exercise hasn’t been impacted by any form of treatment. If your normal intensity level is high, there’s nothing to stop you from maintaining that, but do keep in mind that pushing yourself to always go longer, lift heavier or walk/run faster can be a recipe for disaster.

Just because you CAN up the intensity doesn’t mean you SHOULD; there’s absolutely nothing wrong with maintaining a baseline level of fitness. And should you not listen to your body and injure yourself from overuse/relentless intensity?

You won’t be able to do anything.

Besides, not everyone needs (or wants) to be a marathon-running, power-lifting beast.

But wait, you say. Isn’t it better for reducing recurrence risk to work out harder?

There’s interesting research suggesting that higher exercise intensity may offer greater benefits, especially for reducing risk of breast cancer recurrence, yet the MOST IMPORTANT take-home message about exercise and breast cancer is to do something that gets you moving, more often than not, REGARDLESS of intensity. (2)

The Case For Highlighting Intensity And Breast Cancer

The REACT Study – This 2015 study (Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy) looked at the effects of high intensity (HI) and low-to-moderate intensity (LMI) exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors, concluding that shortly after completion of cancer treatment, both HI and LMI exercise were safe and equally effective at reducing general and physical fatigue. This study supports information I shared in Part I of this series, that there may indeed be a dose-response relationship favoring benefits of HI exercise. (3)

The EXCITE Study – This 2010 “Exercise Intensity Trial (EXcITe)” of 174 postmenopausal women who had completed adjuvant (therapy applied after initial breast cancer treatment) therapy compared moderate-intensity aerobic training to moderate to high-intensity aerobic training and its effectiveness on aerobic capacity, physiologic mechanisms and biomarkers in women with operable breast cancer. Cardiorespiratory fitness may be markedly reduced in breast cancer patients, and this study investigated outcomes to help inform exercise guidelines to address this frequently compromised parameter of health. (4)

The PACES Study – This research compared the effectiveness of a low-intensity, home-based physical activity program (Onco-Move) and a supervised moderate-to-high-intensity combined resistance and aerobic exercise program (OnTrack) to usual care (UC), which varied according to hospital guidelines and preferences, but didn’t involve routine exercise. The trial focused on maintaining or enhancing fitness, minimizing fatigue, enhancing health-related quality of life, and optimizing chemotherapy completion rates in patients undergoing adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Results showed that the supervised moderate-to-high-intensity combined resistance and aerobic activity program (OnTrack) was most effective, yet the home-based, low-intensity program was a viable alternative. (5)

Clinical Trial; “Effect of Low vs Moderate-intensity Endurance Exercise on Physical Functioning Among Breast Cancer Survivors” – This is an ongoing clinical trial (estimated completion date February 2020) at the University of Puerto Rico. 142 breast cancer survivors will be educated on a home exercise program to be performed at either low or moderate intensity. The study’s purpose is “to evaluate the effect of two exercise programs: 1) a program at low intensity; 2) a program at moderate intensity.” (6)

Tips and Take Away’s

There are many more studies looking at this important connection; it’s clear that researchers are intrigued by the impact of different exercise intensity levels on breast cancer prevention, treatment, management and survivorship.

Here are some ideas to consider:

- If increasing exercise intensity feels like too much, increase the duration of your exercise instead (and vice versa). For example, if walking at a fast rate for a shorter time is too difficult, maintain a moderate pace for a longer amount of time.

- Sometimes one “type” of exercise feels better than another. For example, because you can sit down while strength training, it may win out on a day when walking feels like too much (or you’re short on time). You can increase the intensity by lifting heavier weights which will off-set a temporary adjusting down of your walking intensity.

- Don’t stop moving, even during/after treatment if you can. Whatever amount of exercise you can tolerate will aid your body in healing and improving.

- On days you can manage only 10 minutes of exercise, do it! It’s always better to do a little bit of something than a whole lot of nothing.

- Use the chart below to gauge the intensity of activities and exercises you engage in regularly – you might be surprised.

CLICK HERE and get my FREE Nutrition & Fitness JUMPSTART Worksheet.

Sources

- What is Moderate-intensity and Vigorous-intensity Physical Activity?

- Can Exercise Reduce the Risk of Cancer Recurrence?

- Randomized controlled trial of the effects of high intensity and low-to-moderate intensity exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors: results of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study

- Rationale and design of the Exercise Intensity Trial (EXCITE): A randomized trial comparing the effects of moderate versus moderate to high-intensity aerobic training in women with operable breast cancer

- Effect of Low-Intensity Physical Activity and Moderate- to High-Intensity Physical Exercise During Adjuvant Chemotherapy on Physical Fitness, Fatigue, and Chemotherapy Completion Rates: Results of the PACES Randomized Clinical Trial

- Effect of Low vs Moderate-intensity Endurance Exercise on Physical Functioning Among Breast Cancer Survivors